It amazes me that so many documentary makers fail to heed the principal lesson of Asif Kapadia’s Senna, which is that any relevant archive footage, however scrappy, is more interesting than a talking head. It’s a pity that James D. Cooper didn’t learn it before he started putting together Lambert & Stamp, his film about the two men who managed the Who from their first success in 1964 until the relationship broke down in acrimony 10 years later.

It amazes me that so many documentary makers fail to heed the principal lesson of Asif Kapadia’s Senna, which is that any relevant archive footage, however scrappy, is more interesting than a talking head. It’s a pity that James D. Cooper didn’t learn it before he started putting together Lambert & Stamp, his film about the two men who managed the Who from their first success in 1964 until the relationship broke down in acrimony 10 years later.

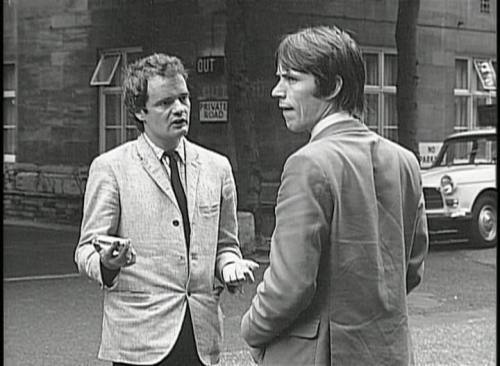

A compelling subject is enough to carry the first half of the film. After that the viewer tires of extended close-ups of Pete Townshend, Chris Stamp and Roger Daltrey sitting in hotel rooms or studios, even when they’re saying interesting things. The archive clips are chopped up and edited fast on the eye, to borrow Bob Dylan’s phrase. Too fast, in fact. The eye wants to rest on them, to be given time to absorb the details. A technique wholly suited to the titles of Ready Steady Go! is not appropriate to this very different project. The exception is a wonderful piece of footage of Stamp and Kit Lambert encountering Jimi Hendrix and Chas Chandler in a London club, possibly the Ad Lib or the Bag O’Nails; we do get to look at that properly, thank goodness.

It’s a story that certainly deserved to be told. Stamp — born in London’s docklands, the son of a tugboat captain — brother of Terence, the male face of ’60s London — almost as good looking but sharp and tough, with more front than Harrods. Lambert — Lancing, Oxford, the Army — the gay son of a celebrated English composer — explaining mod culture to foreign TV interviewers in fluent French and German — empathising immediately with Townshend’s latent talent and Keith Moon’s very unlatent lunacy.

A pretty bruiser and a bruised prettiness: it was a potent combination. “I fell in love with both of them immediately,” Townshend recalls. It’s easy to see how he and, to varying degrees, the other members of the Who were jolted into self-actualisation by the vision and audacity of a pair of energetic wide boys whose real ambition was to get into the film business and who initially saw the music as a vehicle for their ambition.

The viewer does not come away with the impression that the whole truth about the break-up in 1974 has been told, and a few other salient features of the story have gone missing. One is any acknowledgment of Peter Meaden, their first manager when they were still the High Numbers: an authentic mod who helped establish their direction. Another is Shel Talmy, the producer of their first three (and greatest) singles, given only a passing and mildly derogatory mention, without being named.

Lambert died in 1981, aged 45, worn out by his destructive appetites, although the immediate cause of death was a cerebral haemorrhage following a domestic fall. Stamp had conquered his own addictions long before his death in 2012 at the age of 70, having spent many years as a therapist and counsellor. His interviews with the director are used extensively but, lacking the matching testimony of his former partner, his wry eloquence inevitably seems to unbalance the narrative.

At 120 minutes, the film eventually feels bloated. If the first hour passes like a series of three-minute singles, the second is a bit of a rock opera, the occasional interesting fragment separated by long stretches of filler. But, of course, anybody interested in the era should see it.